The implications of our time browsing the Internet

Computer

programs can extract an extraordinary and frightening amount of data

from our web activity. Following the digital revolution and the

proliferation of digital record keeping, the information generated by

our online activity has potentially great benefit, but leaves serious

questions unanswered regarding our confidence in digital record keeping.

As

the world becomes increasingly interconnected and technological

adoption rises in emerging markets, data from online activity poses

great promise and peril. According to studies from the Pew Research Center,

there has been a significant increase in the number of internet and

smartphone users in developing nations. In 2013, across 21 emerging and

developing countries, a median of 45 percent of respondents used the

internet or owned a smartphone. In 2015, the median rose to 54 percent, with much of the increase driven by emerging economies like Malaysia, Brazil, and China.

Through machine learning algorithms, we can now make well calculated

and informed policies with previously unimaginable amount of data from

observing the activity of the newly connected. With the massive increase

in smartphone ownership among residents of developing nations,

passively collected digital data could come to replace household surveys

in assessing social and economic well-being. Information from online

data collection could thus be translated into more effective policies

and better service delivery.

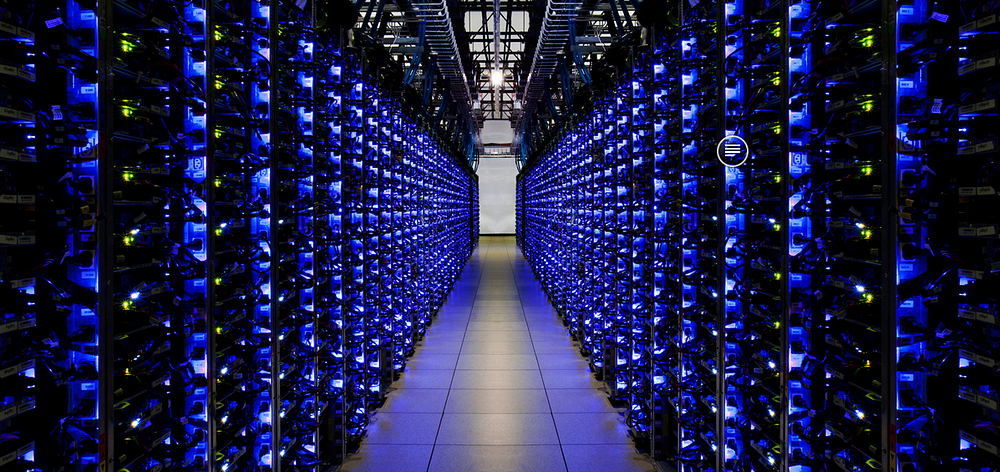

Organizations

such as Google, Amazon and Apple already collect data and invest

heavily in technologies like big data, supercomputers and artificial

intelligence and can tailor information directly to users. Facebook, for

example, measures users’ links clicked, and by studying billions of

data points it can determine the type of news a user might “like” and

push that to their Facebook feed. Though this is an effective way to

personalize the web, society must consider the ethics and implications

of tailoring information, as the loss of reliable and authoritative

information sources can inflame emotions and undermine reason.

In China, the nation is experimenting with “citizen scores”,

which will rank citizens and could determine the conditions that

citizens get loans, jobs, or travel visas. People’s internet activity

and the behavior of their social contacts could potentially be

monitored. Based on different data points, a user could be categorized

over petabytes of information and millions of other users. Conceivably,

without needing any consent or active inputs by the user, computer

programs could guess preferences, estimate income, profession,

educational level, and numerous other details. Algorithms can learn to

recognize life events like pregnancies or even whether you’re thinking

of getting married. GPS location can determine exact locations, home

addresses, and commute time. Programs even have the capacity to predict

your age based on mouse movement; younger people have more precise

movements than older people.

We

begin to better understand complex relationships in the world by

applying algorithms and statistical methods to interpret the figures,

names, and other quantities of online activity data. However, all this

necessitates democratic technologies for greater transparency, trust and

systems that are compatible with democratic principles. This requires

decentralized information systems, commitments to open data strategies,

reduced distortion of information and even granting citizens the right

to get a copy of personal data collected on them.

Utilizing

information aggregated through online activity and translating it into

big data, we can quickly and intelligibly shift through millions of data

points to extract meaningful relationships in complex economies,

national systems, and human behaviors. Data gathering through online

activity and employing big data techniques can be an extremely effective

method for understanding and describing the world, yet as citizens, we

must determine the extent and limit to the data we allow to be collected

on us, how it’s collected, and who could have access to it. Policies

and regulations for which governments and private industry must abide

should be ahead of this technological change, as these algorithms are

already creeping into every aspect of our lives.

0 comments:

Post a Comment